JEREMY GLOGAN

Conversation #1

This conversation, with the London-based artist Jeremy Glogan, emerged from a rather dumb idea: wouldn’t it be funny to do “Jeremy Glogan by Jeremy Gloster”? An interview playing on the similarity of our names, but also gently mocking the naming conventions of other, more self-serious interviews, not to mention self-aggrandizing memoir titles (Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, for instance, or the fictive Tár on Tár)? During this process, I discovered that Glogan had already riffed on this particular joke before – six years ago, he published a fanzine called Jeremy Glogan by Jeremy Glogan as part of Victor Boullet’s series for Antenne Publishing – but by then a stronger sense of his oeuvre had already taken hold.

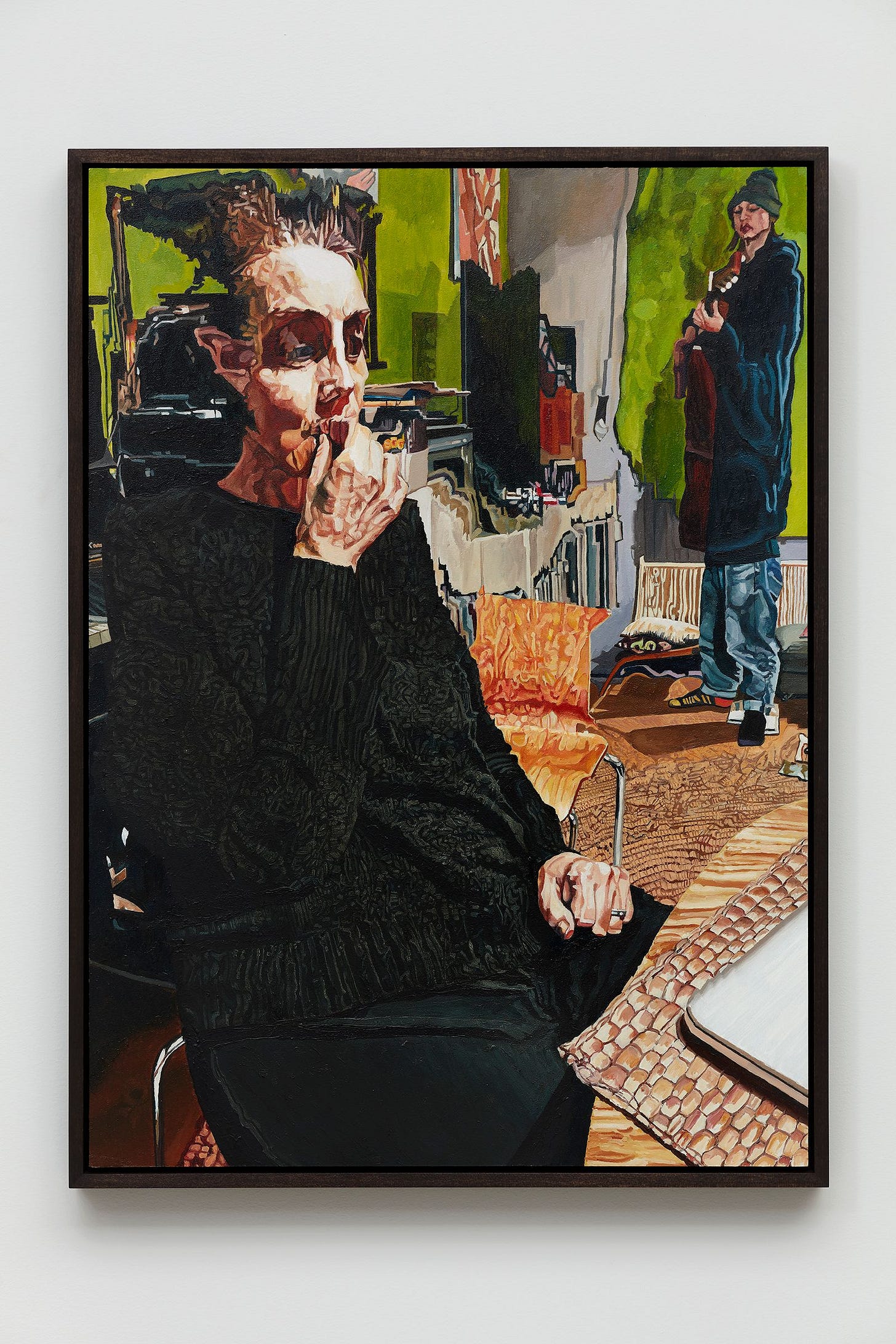

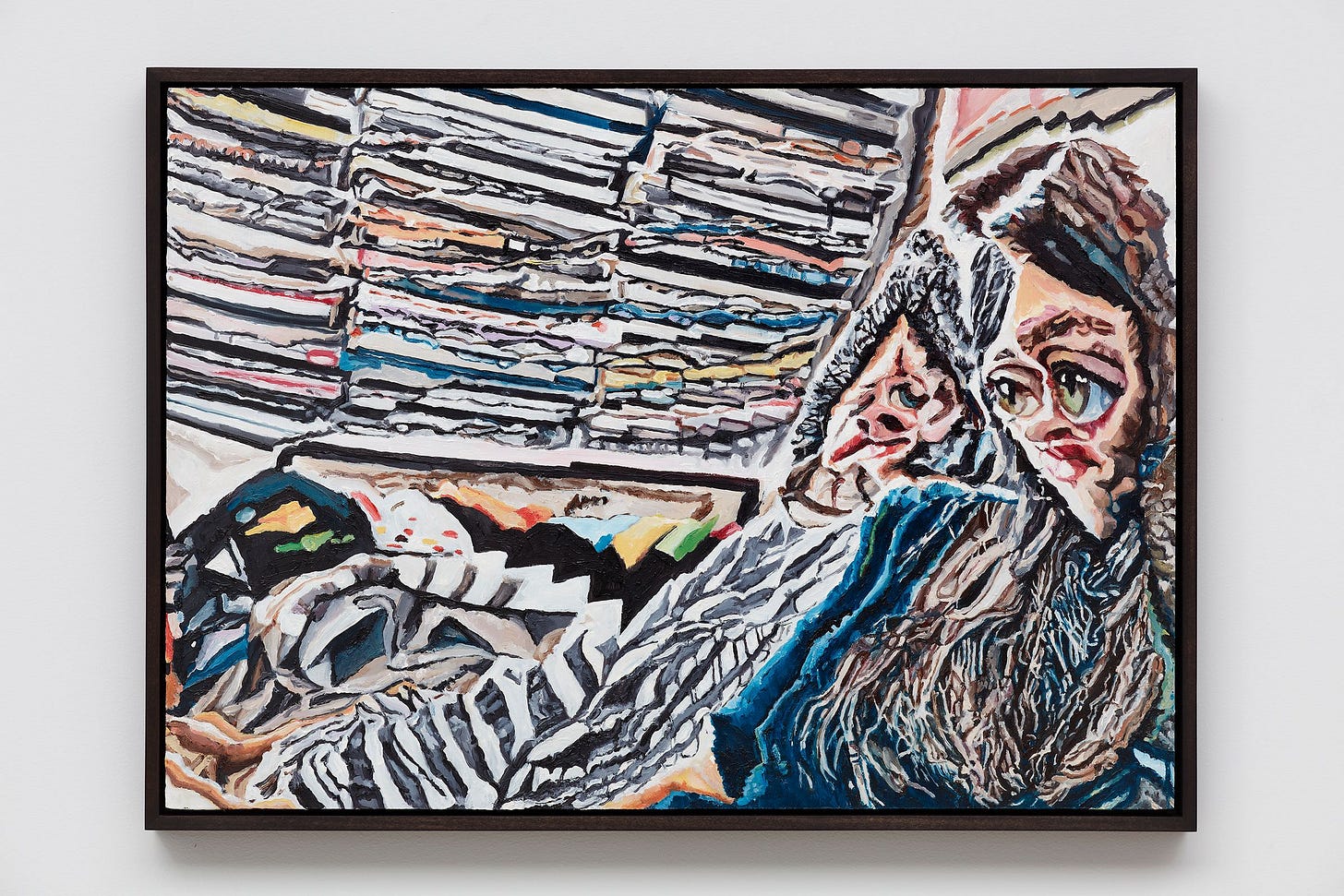

Since the 1990s, Glogan has developed an idiosyncratic, reflexive, and sometimes prescient approach to painting, obscuring the potentially false binary of abstraction and figuration, and, in shifting stylistically from one exhibition to the next, unsettling, maybe, set expectations surrounding individual authorship. Perhaps relating to the latter inclination, there has also been much nominative play – a 2012 exhibition, for example, was titled The Jeremy Hunt for Culture, alluding to the conservative British MP, and another, earlier show, called GLOGAN, included a promotional flyer in which the artist’s name was set, brand-like, against a collage of fashion photography. Yet starting around 2019, Glogan’s work has become markedly consistent, documenting a post-Brexit, post-pandemic social landscape filtered through a series of digital and analog procedures. Although by turns irreverent, sentimental, and humorous, this work has also felt urgent, leaning into to the textures of contemporary life at a moment in which younger artists, specifically painters, have more often chosen to retreat into historicist or post-postconceptual modes of production. Almost notoriously, Gen X artists, or at least the ones we enjoy, have been characterized by a sense of withholding – by both a resistance to historicization and an unwillingness to engage with whatever may come after them – and for this reason Glogan’s participation in spaces like Jenny’s or Le Bourgeois appears conspicuously generous. It’s a form of generosity that extends to this wide-ranging conversation, as well. Over Google Docs, we discussed Glogan’s recent work, the mediational capacities of painting, his position vis à vis a number of tendencies, and his sustained engagement with Lyotard’s sublime. Aside from some light copyediting, the text below remains unedited and unabridged.

JEREMY GLOSTER

Maybe we could start by discussing Leanings, your current exhibition at Jenny’s in New York. This show, in a sense, strikes me as a continuation of your past two solo exhibitions, both in London – While My Paintbrush Gently Weeps at Leech, and The New Distortion at Le Bourgeois. Each predominantly features human figures, a high-contrast color scheme, and seems to arrive at the finished work through similar strategies. But I also wonder if my assessment is wrong – if the stylistic continuity across these three shows, which hasn’t always been a given in your practice, occludes important differences among them. I know, for instance, that this body of paintings took some time to come together, which might suggest that it is, in fact, distinct – that there was a relation to be worked out among the paintings on view. Or it might only suggest that these works are time-consuming to execute, which is certainly true for many artists, and for many painters in particular. Perhaps you could speak to this a little bit, and also to the concerns of this show specifically.

JEREMY GLOGAN

It does represent a continuation of the last two shows. There’s been a formal development within the painted detail led somewhat arbitrarily by better lights in the studio, smaller brushes and remembering to wear my glasses whilst working.

The process to create the work for all three shows involves finding appropriate images and manipulating them – both digitally and through painting. By “appropriate” I mean either in terms of a content that fits together through either the fabric of the original content in the photo or merely by the way it becomes manipulated. The original image content in Leanings may have come from the domestic environment – however for me this represents just a strand within the work.

In relation to stylistic and strategic continuity I have found myself adhering to a similar working strategy for the last 5 or 6 years now – as you point out something that hasn’t often happened in my work previously. There was a moment in 2019 when I manipulated an image and the result genuinely surprised me. This moment is still proving to be consequential.

GLOSTER

And what about the title, Leanings? I actually find this to be one of your more opaque show titles, and the titles seem integral to the exhibitions – sometimes they are straightforward descriptions (Trees by Jeremy Glogan, for instance), yet more often they offer a lens through which to view the work.

GLOGAN

Titles are always lenses. Leanings is a word that suggests to me slight or perhaps insignificant movements or intentions. Leanings can be the result of often instinctive, perhaps not fully considered urges or impulses. The resultant effect of Leanings either in politics or within any creative, economic or social project can have much bigger consequences. I suppose it depends on the angle and trajectory of the lean – how far one leans and in which direction.

GLOSTER

One more question before we really get going. Could you explain your process for these works – how do they come together? I could be wrong here as well, but my inclination is to say it’s almost a parallel activity to this conversation: in a sort of piecemeal way, we’re building toward the image of an interview, an image that likely differs for each of us, and in doing so, we’re necessarily producing all sorts of glitches, misrepresentations, and gaps in understanding. In both cases, it’s not a simple matter of transcription.

GLOGAN

I locate what feels like a pertinent image, manipulate it digitally looking for appropriate often unexpected results, if an image gets past this stage then I paint it. The painting stage appears as the closest step to transcription but of course the brush introduces irregularity. Glitches, gaps and misrepresentations certainly occur throughout the process, and generally are to be encouraged.

GLOSTER

At the same time, the effect of the paintings is not entirely one of pictorial construction, but also of mediation. I was happy to see this word in Daniel Neofetou’s exhibition text for Leanings, because it confirmed my initial impression. It’s almost as if there’s something situated between us, as viewers, and the interior space of the painting, some source of interference occurring at the picture plane. And I think certain works of yours would suggest this reading, as well. The Glass, 2021, for instance, features a subject looking at his hand through a glass of water, and that struck me as a sort of interpretive key. It suggests that we, too, are looking through the glass, at least allegorically. I’d like to perhaps place this idea into contention with Neofetou’s statement from the Leanings text that, “The conditions of possibility for painting are always a series of mediations. These mediations are a successive series of nows.” We’ll get to now-ness later, so maybe we could stick with mediation for the moment. I’m curious as to why you would choose, particularly over the past five or so years, to emphasize the fact that painting is always a mediated encounter. Why insist, on the level of form, that what we’re seeing is, fundamentally, mediated by the artist?

GLOGAN

I was talking to Daniel about the text for the show and that I wouldn’t want any description of the figurative content within the work. Daniel agreed and proposed a text on the “conditions of possibility” for painting. When he says “the conditions of possibility for painting are always a series of mediations,” this suggests that the necessary frameworks for both the production and reception of painting will always necessitate intermediary influences or “mediations.” Within both production and reception these influences will be various and profuse within all conceptual and formal aspects of the painting. Perhaps this is self-evident, but this idea of mediation or the notion that things are not self-contained and have to exist in relation to or through something else seems infinitely simple and I think infinitely useful.

Incidentally, as the figurative content of the work exists in its mediated pictorial form I think it would be thrown off balance by any verbal description.

GLOSTER

The first paintings of yours I saw in person were those included in Sex is [Censored] Part 3: Le Pissoir du La Perle, which was a sort of crazy group exhibition curated by Zac Segbedzi, again at Jenny’s. I remember being taken by this work, a relatively small painting in the show, titled The Gherkin, 2010. It’s a painting of the London skyline, or the skyline of London’s financial district, with your face reflected in the Gherkin, which is, of course, one of London’s most recognizable skyscrapers. You essentially become the Gherkin. And I’ve tried to articulate why I’m drawn to this painting – it certainly encompasses some of my preoccupations with the functions of architecture and photography, mirrors or mirroring, perhaps even the hyper-financialization of art, and there’s a certain cultural acuity at play for you to have thought to make this painting in 2010. But my reasoning falls flat; it feels like explaining a joke. There’s a sense that all of these complex ideas are being compressed into this deceptively simple, maybe even deceptively stupid, image. I really like when art does that. But, to get back on track, you seem to insert yourself into your work fairly often, and often in ways that seem more conceptually driven than, say, a conventional self-portrait, and I wonder where that impulse comes from?

GLOGAN

I’m not totally sure where the impulse comes from, however the “stupid” and the “dumb” can be great if used well. I remember having the idea for the Gherkin painting and thinking that it was so ridiculous that it might just work. It was post-crash, I wanted it to appear as if, yes, I actually was the Gherkin – within the city – looking distinctly displeased. It did feel edgy to play with an actual self-portrait like this in 2010, because it was so silly. This was just prior to selfie culture really taking off and I think just as perhaps Jana Euler or Amelie von Wulffen started to play with anthropomorphised themes.

GLOSTER

Another instance where architecture enters your work is Building, 2021, and it’s also a feat of compression. It depicts Eros House in south London, a Brutalist building designed by Rodney Gordon and Owen Luder, and Brutalism is always a charged form in the UK – it’s almost a spectral presence. It points temporally in two directions: to the past, because its emergence as a style of postwar reconstruction is inseparable from the ravages of war, and also to an unrealized future, because it embodies the failures of both social policy and modernism. But then, to add another layer, Eros House isn’t wholly of your own choosing, either. It comes almost as a ready-made subject, because you’re painting the building where the gallery Le Bourgeois is located and where the painting will later be shown. So there’s a telescoping effect here – from general to highly specific – that I think becomes synecdochal to the larger project. You paint people you know, but these subjects are embedded in a set of social conditions that might lead us outward, toward other cultural associations and reverberations. In an ambient kind of way, for example, I’m often put in mind of Mike Leigh films like High Hopes or Meantime, which might suggest a certain tonal resonance. So I’m interested in how this decision to assert this sense of sociality – or, perhaps, to reassert it, because you also certainly painted people you know in your earlier work – plays out? It doesn’t feel aligned with other modes of social painting like “hypersentimental portraiture” or “network painting,” although perhaps it may operate similarly – the closer we are to you or your particular social context, the more we recognize in your work.

GLOGAN

Eros House is quite a difficult site. It’s situated in the middle of a gyratory system around which fairly heavy traffic continues day and night. It’s in a tougher part of South East London that has resisted gentrification. The once quite handsome Brutalist building was insensitively re-clad in the 80s and I believe that Owen Luder then disowned it. It was optimistically named “Eros” after the Edwardian theatre and cinema that once stood on the site. Catherine Osterberg and Jacques Rogers established and ran the project space and gallery Le Bourgeois in a former restaurant unit on the ground floor from 2016 through to 2023 and staged around 30 great shows there. My studio was in the back room. There was a good social scene attached to it. Some members of this scene including, as you say, the building itself, became part of the content for my work in The New Distortion in October 2021.

I don’t think that the inclusion of specific people and subjects who I know has ever really been a conscious strategy, more that in the search for content the more familiar subjects seem to have the most appeal simply because I am more closely acquainted with them. I think that the distance created by the mediation within the work enables more intimate content to be presented.

GLOSTER

In Kari Rittenbach’s review of The New Distortion, she lands on this indelible turn of phrase: “‘bad painting’ finally meets ‘bad utopia.’” There’s actually much happening in that concise formulation, so I’ll structure this as a two-part question – we’ll once more separate bad from bad. I’ll start with “bad painting”: certainly this term carries meaning for many artists with whom you are either close or have collaborated in some capacity over the years, but your own relationship to this lineage – which we might consider, for this conversation, as a lineage after Kippenberger – is less clear to me. I’m tempted to cite your earlier exhibition The Paintings I Did Before the Exhibition, at Galerie Bleich-Rossi in 2008, as a particular moment of “bad painting,” indicated by the deadpan title and the relative sparseness of the compositions, but I’m not sure you would see it that way.

Relatedly, there’s the notion of “ugly painting,” which was more recently coined by Rachel Wetzler in describing the work of Jana Euler, and which Wetzler expressly distinguishes from “bad painting.” For context, I’ll quote from her essay: “Bad painting approaches the medium as something that can only be pursued ironically, through a posture of carelessness, haste, and disregard. Its ugliness is of the second order, an effect of its ostentatious repudiation of proficiency… ugliness here is a choice, and a deliberate one… self-evidently labored over, made slowly and precisely. Their features may be repellent, but there is no mistaking them for slapdash accidents.” Your paintings have been associated more closely, I think, with this tendency – you were, for instance, included in the group exhibition Ugly Painting, organized by Eleanor Cayre and Dean Kissick, at Nahmad Contemporary in 2023. But I wonder how these ideas intersect or correspond with one another for you? Or if you would reject this framework entirely?

GLOGAN

Of the various strands of “bad painting” the one I was more aware of is the German one originating, I'd actually say, from the 1960s onwards. At art school in the late 80s I started to pick up on the Oehlen brothers, Kippenberger, Walter Dahn, Dokoupil, Schnabel and maybe even Steven Campbell at the same time as the earlier generation including Baselitz, Immendorff and Polke. I enjoyed the irreverence, wit and satire alongside the painterly physicality. Merlin [Carpenter] and Krebber’s approaches (for example) went on to diversify and create further nuance within the lexicon and, as I knew them personally, I was able to witness some stuff at first hand. So I think that in my approach there has always been something of the irreverent attitude of “bad painting” and I see this as much in the “figurative” work as the “abstract.”

It’s amusing this notion of Ugly vs. Bad painting and the question of which order the “ugliness” is presented within. I know what she’s implying but the discussion for me is not so interesting. Good painting rarely depends on how it looks in terms of a discussion of bad or ugly. Good painting will always be beautiful!

GLOSTER

That’s really funny, and I think you’re right – many of the works in that group show may have actually encouraged us to reach that conclusion. But, to address the first part of your response, what was the reception to these artists like at art school in the UK? Were professors supportive or was it sort of a provocation to engage with them this early on?

GLOGAN

Just as we were starting our first year at Camberwell I remember a tutor, Ian McKeever telling us that the big Julian Schnabel show that had opened that week at the Whitechapel was the most important thing we could see. McKeever, who had spent time in Germany went on to tell me about Mulheimer Freiheit of which Dokoupil and Dahn were part of and, I think, Kippenberger and the Oehlens. Alongside my interest in Steven Campbell – the best and “baddest” of the new Glasgow figurative painters this provided me with food for thought. So yes, I happened to have a supportive tutor. Friends who’d been at St Martin’s including Merlin were so interested in Cologne that on leaving art school they went straight out there to live and mix with the scene.

As a student deciding to engage with this emerging language I suppose could have been somewhat provocative by default. Although the “New Spirit in Painting” was hovering throughout the 80s and the “bad painters” began to emerge from the mid 80s, perhaps the nuanced language of “bad painting” wasn’t yet fully born – at least more internationally – until the early to mid 90s. I think somehow Gilbert and George, although not painters, always offered a UK contextualisation of a “bad painting” attitude in terms of wit and irreverence and perhaps scale of project. Interestingly they’ve always been able to take the position of rebel at the same time being fully accepted by the establishment.

GLOSTER

And then “bad utopia,” which might return us to the question of mediation. I’m not quite sure what Kari meant by this, although it is rather evocative. She may have been thinking of this line from Terry Eagleton, which does hold some resonance: “‘Bad’ utopia persuades us to desire the unfeasible, and so, like the neurotic, to fall ill of longing; whereas the only authentic image of the future is, in the end, the failure of the present.” So it might be closely related to Lauren Berlant’s concept of “cruel optimism,” and, in your work, to the cruel optimism of the social world you’re representing or mapping. I’m interested in what you’d make of that.

GLOGAN

Yes, I like the way it’s not entirely clear what Kari means. I feel perhaps she is referring to the mood of the pandemic and the fact that the show happened to coincide with that and, yes, become mediated by it. There was the posited utopia enabled by societal shutdown which was in fact “bad” in terms of ill health and the manifesting of further social imbalance.

GLOSTER

Yet I would think the recent paintings have more in common with the anti-utopian, at least as it’s framed by Linda Nochlin in The Politics of Vision. I think of Nochlin’s claim that “if Seurat rather than Cézanne had been positioned as the paradigmatic Modernist painter, the face of twentieth-century art would have been vastly different.” What Nochlin suggests is that if artists had received Seurat’s message – the “anti-utopian allegory” of Pointillism, in which the faux-industrial pictorial construction appears to comment on the depicted scene, as in A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte – art would have been different. This strikes me as a strand of the modernist project you take up, at least recently. It’s not about placing a machine or device between the artist and the canvas – as many artists over the past sixty years, from Warhol and Jack Whitten to Rosemarie Trockel and Wade Guyton have done – but rather about embedding a sort of machine vision allegorically within the work. I’m reminded – in paintings such as Seasons, 2024, and Buggy, 2020 – of digital editing processes like image-stitching, or, like, that strange stuttering effect that can happen when one tries to make a panoramic image on an iPhone. There’s an even more frequent rendering effect reminiscent of pixelation, but it almost seems to derive from digital video, rather than low-res imagery. Elsewhere, I think of the figural malformations sometimes produced by text-to-image generators. So I’ll ask – and I’ll actually ask a question this time – how do you perceive distortion to operate within your work? Is it about inhabiting a kind of technologically-mediated position or is it more of a painterly means to reconcile abstraction and figuration? Is it related to digital imaging or does it emerge from someplace else?

GLOGAN

It is interesting to compare Seurat and Cézanne in this way. As a painting process Pointillism was certainly less dynamic, a bit more considered than Cézanne’s application. If you compare La Grande Jatte to say Les Grandes Baigneuses they’re equally experimental within their respective discourses. Cézanne is much rougher at the edges in terms of finish. I think that Seurat became obsessed with his application, preciseness of composition and the utilisation of his scientifically informed colour knowledge. Cézanne obsessed about looking, looking again and interpreting. In terms of Manet – as precursor to both – and his formal leanings toward the acausal, perhaps Seurat was more prepared to both absorb Manet’s radicalism but then reject him formally while Cézanne enthusiastically ran with him and attempted to go beyond. I had never considered the utopian implications of Pointillism, but that’s an interesting idea.

Considering the distortion in my work. As I said there was a moment in 2019 when I digitally manipulated an image and the result genuinely surprised me, this became the 2019 painting Beard. It created a point of reference from where I’ve continued to work. Looking at the Seurat again, it is interesting to think about the picture’s considered construction together with his interest in scientifically informed colour theory. Unlike Cézanne there is a much more measured, I think you could say “technologically mediated” process taking place on the canvas. I would say however that Seurat’s dots are surely not actually “atomic” as Nochlin suggests – they surely have to rely on other relations/mediations.

There’s nothing conscious for me about reconciling abstraction and figuration, it’s very much about remaining in the painted zone and the mediation of the digital enables that.

GLOSTER

It would be good to discuss some ideas or arguments that have informed your practice, as well. And you’ve told me that one such argument comes from Jean-Francois Lyotard’s essay “The Sublime and The Avant-Garde,” which was originally published by Artforum in 1984, and it’s also something Daniel Neofetou engaged with while writing the exhibition text for Leanings, as well. There’s much to unpack here, but I thought I would give you the chance to speak first. Why have you, as you say, held onto this text for so long?

GLOGAN

It’s a good question! The text could be seen as somewhat anachronistic and sometimes open to interpretation. A good friend once introduced me to it. I’ve kept it with me as it does continue to throw up interesting ideas. By chance Daniel Neofetou had been considering some of Lyotard’s thought and when discussing the text for the show it became clear that some reference could be made to this.

Lyotard was aware of Barnett Newman’s concern with “a sensation of time” within his work. A concern with time beyond even image or space. Lyotard speaks of a contemporary sublime linked to this “sensation of time” within the otherwise “inexpressible event” that is a painting. I like how this creates an idea of painting as a process linked specifically to time and that somehow liberates it as an activity. The act of painting in itself could represent this sublime feeling that Lyotard claims to be potentially radical. Lyotard takes the idea of “now” as the ungraspable moment or occurrence that exists only in the future or in the past but can be formulated, he suggests, as “a question mark,” the question mark of the “is it happening?” He talks of the search only being possible if there still exists something that hasn’t yet been determined – “the indeterminate.” He also suggests that this event or occurrence, the “now” can only be “approached through a state of privation…that which we call thought must be disarmed.” Crucially he takes this potential and imagines it in a position of resistance against an “over-capitalised” society. He seems to suggest that this contemporary notion of the sublime offers a space of resistance to capitalist modernity which is enforced by a total control of knowledge. Newman’s moment embodies an evasive state. In resisting that which can be known there is a possibility of resistance to this form of knowledge as regime.

I think that the “nows” as mediations in Daniel’s text are analogous to Newman and Lyotard’s “nows.”

GLOSTER

I was actually thinking while reading it that it’s one of those texts that seems useful to return to repeatedly because I can see how some passage, or even a single sentence, that may have not seemed so important before suddenly feels relevant to what you’re working on in the moment; its sort of “openness” is actually a strength in that sense. And I actually don’t think it’s entirely anachronistic, either; Peter Osborne has often been influential for me, particularly in his theorization of the contemporary, and I realized Osborne is drawing on Lyotard’s notion of the present as an indeterminate conjunction of past and future. And I think that sense of indeterminacy, which may be something like “historical mediation,” really comes through in the work; in different terms, it was one of the first things I wrote down in my preliminary notes. But I’m curious about this idea of the act of painting itself as perhaps a liberatory or transcendent activity. Is it not labor? Or does it really feel more like this heightened state or “sensation of time”?

GLOGAN

I don’t mean transcendent. And I don’t mean the time or effort taken to make the painting. Lyotard is at pains to stress that Newman’s “now” or question mark of the “is it happening?” is “not a major event…not even a small event. Just an occurrence.”

It’s to do with the idea that Newman implies and Lyotard develops that the act of painting itself could possess radical potential. When I first encountered this text in the late 90s I was interested by the idea that transcendent imagery like mountains need no longer be involved here – painting just had to happen and Newman’s paintings with their bands and areas of colour somehow confirmed this. And I certainly don’t mean that painting is liberated from its necessarily mediated position but that the act of painting, as a fully mediated process, is potentially liberated.

GLOSTER

We might be running out of time to write back and forth, but I thought maybe we could end somewhere else. Your social context seems like it has always been integral to your work, even when it hasn’t been the explicit subject of your paintings, and I think that may form part of its appeal, as well – that it doesn’t pretend to exist in a vacuum and that it’s unequivocally in conversation with other artists that you know. At least since Brexit, one regularly hears this lament that London is no longer the art capital of Europe, but, at the same time, I think London is often romanticized, in New York particularly, as one of the few remaining places where this kind of sociality still unfolds organically. To that point, you also ran a project space in London between 1997 and 2001 called The Top Room, which staged exhibitions by artists like Josephine Pryde, Merlin Carpenter, Nils Norman, and Michael Krebber, among others. Of course, 1997 is a charged year, marked by the ascendance of New Labour and its attendant, if fleeting, sense of cultural renewal. What was the original impetus for The Top Room? Were you trying to fill a specific void or did it come about more spontaneously? And – perhaps more nebulously, although you may have thoughts on this – do you sense any correlations or distinctions between that moment and our current one?

GLOGAN

Certainly if the majority of your friends are artists it’s hard to separate your friends from your work. In terms of the sociality of London it’s hard to be objective as I’ve only ever lived in London, however it’s true that over time social groups and networks continue to exist and flourish.

The Top Room emerged through necessity. I was inspired by Poster Studio, the radical space in a squatted building in Central London run by Dan Mitchell, Josephine Pryde, Merlin Carpenter and Nils Norman in the mid 90s. They created an unprecedented and challenging programme of events and shows. In turn they had been inspired by Stephan Dillemuth and Josef Strau’s Friesenwall 120 in Cologne.

My partner and I live in a building that was part of an old primary school. The top room was the old library, fairly modest proportions; I gradually realised that I had to start a project space there. From 1997 until 2001 we put on a few shows, nearly all friends including Merlin (1998), Nils (2000) and Krebber (2001). We also did a sizeable group show in 2000 (21st Gear) and in 2005 we did a show at Chelsea Space which included a presentation by Mel Bochner.

In relation to ’97 and now – which is 28 years – the world obviously feels a lot less stable now.

The breaking down of the rules-based order and the rise of far-right nationalism are such profound phenomena that were difficult to imagine back then and much harder to imagine in the 70s and 80s, yet the groundwork was being laid throughout that time. Also, it goes without saying, that the internet has changed everything. In 1997, I neither owned a computer or had an email address.