INSIDE BASEBALL

Bad Objects #5: Lutz Bacher

LUTZ BACHER: BURNING THE DAYS (ASTRUP FEARNLEY MUSEET, OSLO)

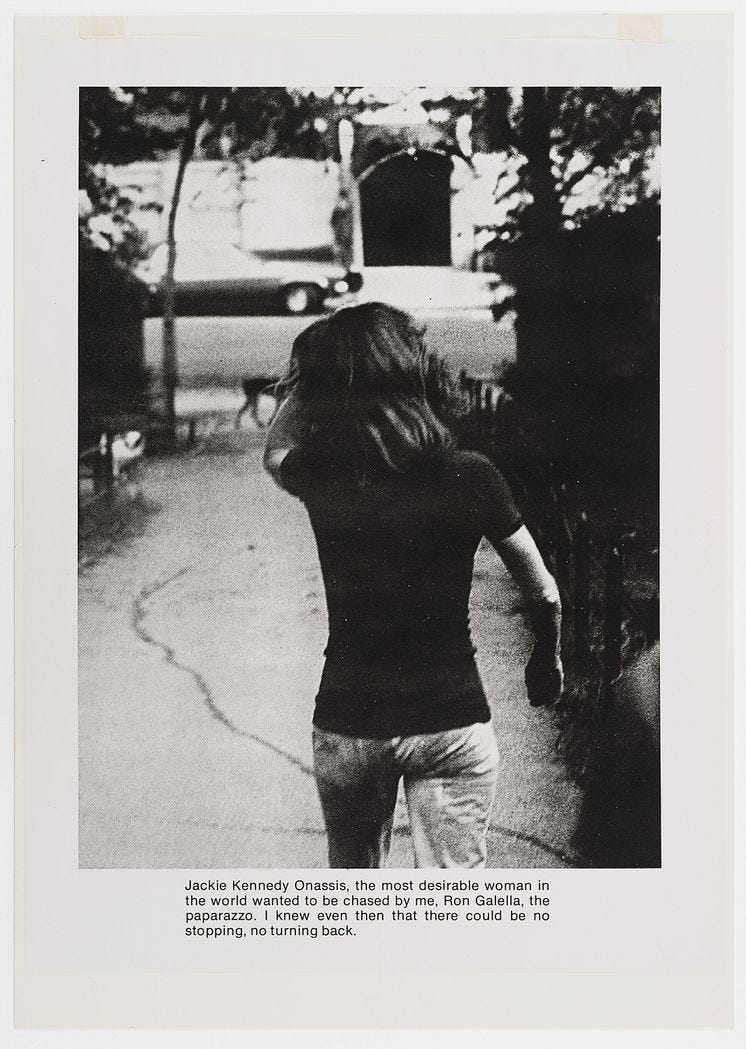

Just look at the promotional images. Images drawn from Lutz Bacher’s photographic suite Jackie & Me, 1989, refashioned as museum advertisements. Plastered around Oslo, on the trams as well as the city’s distinctive nedstigningstårn, or otherwise printed on gift shop postcards and tote bags, they announce the first comprehensive Lutz Bacher retrospective following the artist’s death in 2019. Characteristic of Bacher’s work in general, Jackie & Me is both completely straightforward and dizzyingly complex: the series comprises seven pages lifted and enlarged, without further alteration, from Jacqueline, a 1974 monograph on Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis by Ron Galella, Andy Warhol’s favorite paparazzo. The images depict Kennedy Onassis, atypically clad in jeans and a t-shirt, running through Central Park, given chase by the camera’s gaze. We never catch the photographed woman’s face; if not for the signature hairstyle, a glimpse of the oversized sunglasses, we might wonder if the subject is indeed the real Jackie Kennedy. As in Bacher’s other appropriation works, the images’ accompanying texts are left intact, retaining the gleefully exploitative tenor of Galella’s book captions. (“A woman gave me that ‘get lost’ look––and then I saw Jackie right in front of me!”) Tabloid images complicated by their transfiguration into contemporary art: now they are about something other or larger or broader than bargain bin titillation, although they are still about that, too. Placed in exhibition, successively arrayed as a short narrative sequence, the images form an art-historical riposte – a row of seven evasive Jackies to Warhol’s iconic grid of Nine.

At Astrup Fearnley, the fugitive Jackie also becomes a somewhat obvious stand-in for Bacher herself. From the mid-1970s, Bacher worked pseudonymously, and from the mid-1990s on, she began to eschew the regular demands of publicity required of artists in an age of fax announcements and magazine features. Basic details of her life were concealed, media photos became scarce or obscured, interviews rare, press releases increasingly opaque. Dismayed by a newspaper review that seemed to respond to an accompanying exhibition text rather than to the exhibition itself, Bacher initially set these parameters to encourage a more direct encounter with her work, one unfettered by biographical interpretation or diminished by a reductive application of critical theory. Yet in the absence of an operative public narrative, the act of withholding or obfuscating extratextual information became her paratextual frame, and she toyed with that notion, as well. In one piece on view, Bingo (Or the Year I Was Born), 2008, a large electronic display board is programmed to illuminate numbers at random – all possibilities for the artist’s birth year, retracted from the gallery CV. For another, Do You Love Me?, 1994, relegated to the museum’s website, Bacher compiled a twelve-hour video from interviews with friends and family, artists and art professionals. The subject of the interview footage is invariably Lutz Bacher, yet her on-camera respondents remain undifferentiated, anonymous except to those who knew Bacher personally, or who were well-acquainted with her social milieu. We hear Bacher’s voice, but do not catch her likeness.

While Bacher’s resistance to the celebrity principle of late twentieth-century artistic production might be overstated, in the current literature if not the present exhibition, it could have been interesting had Burning the Days followed this line of inquiry. What distinguishes Bacher from an art world dropout like Lee Lozano, or, for that matter, an intermittent recluse like Cady Noland? Answering the question would require grappling with a number of contradictions. Bacher did not retreat from public view so much as she attempted to exert control over her public narrative, reinscribing it, obliquely, within her work. Two of her earliest pieces – Auto Interview and The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview, both 1976, both transcripts of Bacher talking to herself – set the terms for a form of art in which the artist is somehow simultaneously present and absent, on-stage and off. Toggling between two voices, both Bacher’s, they anticipate a closed discursive system the artist realized more fully in the second half of her career. Yet, from the beginning, Bacher also appeared in front of the camera, in The Milk Video, 1976, for instance, unseen in this exhibition, as well as in the only film-strip piece on view, Smoke, from the same year. Only two years before Do You Love Me?, she made Are You Experienced?, 1992, not on view, a video in which she figures herself as a guitar-smashing rock star. And what does Do Your Love Me? actually do, after all, if not wryly propose Bacher as a proper media subject, someone everyone should talk about endlessly, all the time? If not quite paradigmatic of mid- to late-career Bacher, Do You Love Me? is at least instructive: the deluge of information, the grain of digital media, the positioning of the artist’s limited subjectivity as cultural cipher, the construction of a dialectic Bacher herself referred to as one of “intimacy and distance.” Too much information as its own distancing effect. Information as a form of intimacy. It is difficult to think of an artist who did more to turn her practice into a game of inside baseball, wholly legible only to those who spent copious amounts of time among its recursive evocations, only to those who knew it (and therefore her) best.

In this sense, the prominence granted here to Jackie & Me is again telling, in so far as it suggests its author/subject (mediator?) remains, for this curatorial team, an unapproachable enigma. Deviating from chronological arrangement, the retrospective is instead organized around a number of “associative encounters,” as the gallery guide refers to them, pairing Horse Painting with Horse/Shadow, both 2010, or coupling Pink out of a Corner (to Jasper Johns) 1963, 1991, with The Pink Body, 2017. In one far-off room, the show recycles an installation strategy devised by Bacher for her mid-career surveys MY SECRET LIFE and Spill, recreating those exhibitions’ salon-style intermingling of three discrete series. Such decisions honor Bacher’s delightfully off-kilter (one might say antagonistic) approach to institutional architecture, but they also reveal an aversion toward commenting, in any way, on the work at hand. Likewise, a dearth of supplementary material – whether in the form of wall texts or the artist’s test pieces, preparatory notes, and ephemera – allows the work to stand on its own, but also evinces an unwillingness to provide any sort of historical or social context. Another sign of willful silence is telegraphed by the exhibition title itself, Burning the Days, which refers to an artist’s book Bacher left unfinished before her death, a sequel of sorts to her chronological catalogue Snow, published in 2014. The unpublished manuscript may be viewed at the Betty Center, the artist’s archive slash designated artwork, in New York. Its absence here strangely emphasizes the retrospective’s own hollow center.

What else is missing? Well, all of the artist’s books, nearly every work in video and video installation. The artist’s website, also designated as an artwork, as well as the web-based project Modules, 2017-2019. A few major pieces, including Sex with Strangers, 1986, and Snow, 1999, alongside helpful minor works, like James Dean, 1986, and The Baby, 2012. Without constructing an entirely different exhibition, bringing in some of this material would have introduced a better understanding of Bacher’s distinct visual grammar, the indefinable syntax of which has made her work more influential now than in her own time. (Also conspicuously absent: a sense of Bacher’s habit of retooling old ideas, revisiting certain preoccupations, and restaging past projects, all of which other recent presentations – I’m thinking particularly of the historicizing Lee Harvey Oswald Interview at Galerie Buchholz, from 2022 – deftly elucidated.) As it stands, Burning the Days focuses predominantly on the found objects, sculptural readymades Bacher presented with increasing frequency after 2000. Seen collectively, these objects do further elucidate Bacher’s obsessive fascination with postwar American culture, her prolonged investigation into the quiet reverberations of kitsch and cultural refuse, the secret life of things removed from circulation. There are a few instances in which the associative logic snaps into place. One would not immediately think to pair the stuttering panorama Men at War, 1975, with Bison, 2012, a grouping of sculptures assembled from burlap, wood, and chicken wire. Yet together they tell a story, a darkly American story, of westward expansion and its burlap-thin veneer of moral certitude.

Are such moments of lucidity, however, really enough? Whatever Burning the Days tells us, Bacher did not emerge from nowhere. First submitting a photographic piece indebted to Duchamp, she was initially exhibited in a group show called Photography & Language, held in San Francisco in 1976. She may not have been fully shaped by the group that emerged from Photography & Language, which also included artists like Lew Thomas, Donna-Lee Phillips, and Hal Fischer, yet the early association did enable her passage from photography to conceptual practice. In Berkeley – outside New York, apart from the CalArts mafia – she constructed her own form of post-conceptualism, her own understanding of appropriation. More so than most of her contemporaries, she contended with the shifting position of the photographic image within culture, from tabloid pulp and television to YouTube and content aggregation; she did so for nearly a half-century. Counter many of the Pictures artists, she recognized early on that mass culture, engendered by television and print media, and, later, by the internet, is not solely a one-way street, a top-down system of dissemination. (The series Jokes, 1985-88, for instance, is already an appropriation of a consumer-generated appropriation.) After Derrida, but before Mark Fisher, she came up with an elegiac mode of making, centered around technological breakdown and historical lament, that anticipated, in video, the concept of “hauntology.” She made art that at first appeared slacker-ish, self-centered, or otherwise too easy, but, in actuality, was deeply conversant with histories of modern art, visuality, and the broader culture; she made art finely attuned to the particular textures of contemporary life. It would have been nice had Burning the Days been a little more about that.